Regular measurements of snow depth will help understand climate change. But that might not be the only motive.

File photo of Mount Everest. (Photo credit: Twitter)

New Delhi: Using ground-penetrating radar, Chinese scientists claim to have found a mean depth estimate of more than 9 m of snow at the summit of Mt Everest. This is much deeper than the previously reported values of 0.9-3.5 m.

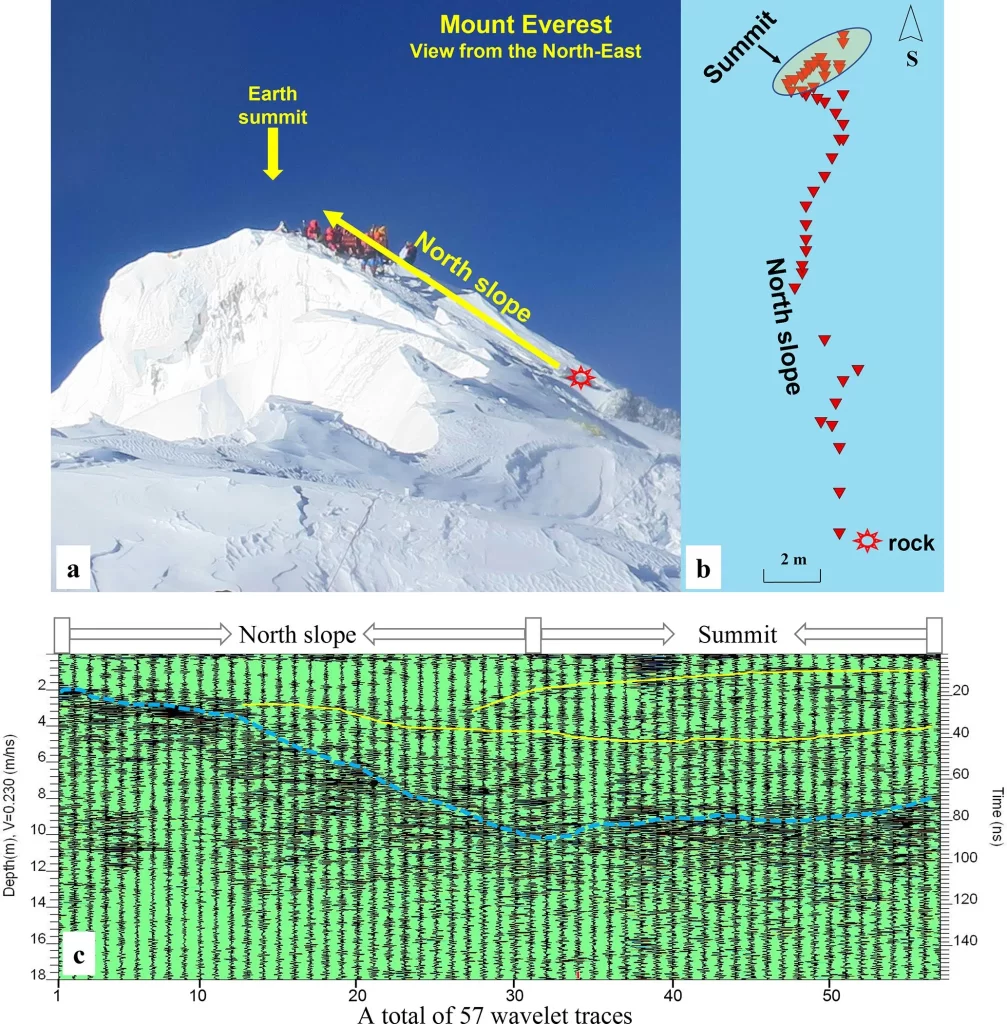

A new study has reported the findings of the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) that carried out the ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey of snow depth along the north slope of the world’s tallest mountain (about 8,850 m) in May 2022. Besides mentioning the snow depth, the scientists have made no claims of it becoming thicker or thinner in recent decades.

This finding assumes significance in view of the recent focus on the impact of climate change on the Himalayas. On the 70th anniversary of Mt Everest Summit, on May 29, mountain communities, glaciologists and mountaineers appealed for concerted efforts at de-carbonising in view of the impact of climate change on the higher reaches of the Himalayas. As many as 79 glaciers – including the iconic Khumbu glacier, which is the starting place for most expeditions – surrounding the Everest have thinned by over 100 m in just about six decades. The thinning rate has nearly doubled since 2009, a November 2020 study said.

The snow depth of Mt Everest, or Mt Qomolangma as it is called in Tibet, is a critical climate canary.

Way back in 1975, a Chinese team used a wooden stake to report an estimated 0.92 m snow depth on the world’s tallest mountain. In 1992, a joint Chinese-Italian expedition used steel stakes to measure 2.52 m. In 2005, a Chinese mountaineering team claimed a snow depth of ∼3.5 m by utilising ground-penetrating radar, but it was not an undisputed depth. In 2019 and 2020, multiple Nepalese and Chinese teams measured snow depths using different radar instruments but reported no results.

The current GPR survey becomes instrumental in filling the knowledge gap. In contrast to the previous radar surveys, this time, measurement started from the exposed metamorphosed limestone at an elevation that was approximately 15 m lower than the summit.

“We applied a novel approach to using GPR technology, by starting measurements from exposed limestone at a lower elevation point, thus resulting in more accurate readings. Our radar measurements display a gradual increasing transition of snow depth along the north slope, and the mean depth estimates at the summit are 9.5±1.2 m. This updated snow depth on Mt Everest is much deeper than previously reported values of 0.9–3.5 m,” said the lead author of the study, Prof Yang Wei of the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

This research, published in the journal ‘The Cryosphere’, was also supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

The team used a Sensor & Software Pulse EKKO Pro GPR system. It was equipped with a single transmitter-receiver antenna and was specially adapted to endure the terrain’s harsh conditions to get more accurate measurements.

This finding uncovers more than just snow depth. It opens a path towards a deeper understanding and the impacts of climate change at high altitudes on the Earth.

What next?

However, the Chinese scientists have also added a disclaimer. “There is still a lack of evidence that the snowpack has become thicker or thinner in recent decades. Future repeated radar measurements at the summit would be helpful for evidencing such dynamic changes under climate change,” the paper said.

The researchers claimed that the measurements “provide the first clear radar image of the snowpack at the summit of Mt Everest”.

“Future snow core drilling and repeated ground-penetrating radar measurements are also necessary, not only to increase our understanding of dynamic snow changes but also to detect the possible influence of unprecedented anthropogenic climate change by exploring the snow stratigraphy and snowpack properties at Earth’s summit,” the study added.

New Delhi-based glaciologist AP Dimri said, “It is understood that accessibility to the Everest Summit is highly restricted because of heavy winter snowfall. But even if they (Chinese) continue to take readings during summer, then it will give at least some kind of indication about snow cover.”

India’s Everest studies

The Himalayas are the veritable Third Pole as they hold the third largest snow and ice deposits outside the North and the South Pole. Ten major rivers, including Indus, Ganga, and Brahmaputra, originate from this region, impacting almost 240 million people across countries.

Unlike the Chinese visiting the Everest region in person for decades, Indian scientists have mostly studied it based on satellite imageries. Indian expeditions to the Himalayas are restricted to 15,000-16,000 ft (under 5,000 m).

“Owing to the high altitude at the Tibetan side, it is easier for China to access the Everest region,” said Dr DP Dobhal, glaciologist, formerly with the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology.

However, it is not a question of funding. “Our scientific expeditions go to Antarctica, Arctic, etc. and for a longer time. So, funding is not a problem. But the Everest region is a different ballgame. Our experiments happen within our side of the Himalayas. Sending people to 18,000 ft+ (over 5,500 m) altitude is not possible. Moreover, it is not a question of a day. It needs concerted efforts,” said Madhavan Rajeevan, former Secretary, the Ministry of Earth Sciences.

In the past, The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) had sent several researchers across the Himalayas to study the depletion of glaciers, including those from the Everest region, but all on the Nepal side. Snow and Avalanche Study Establishment (SASE) under the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) had also carried out a survey, explained Srikanth Kondapalli, Professor of China Studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University.

“China has been putting up 4G and 5G equipment in the Himalayas, including the Everest region. In scientific studies, they keep alluding to the strategic importance. But one doesn’t know exactly what are the strategic aspects involved,” Kondapalli said, adding, “If you are on Mt Everest, the whole of South Asia telecommunication can be monitored. Who will not like that?”

(This story first appeared on news9live.com on Jul 20, 2023 and can be read here.)