State intervention, rainfall have helped improve groundwater situation in water-stressed areas.

MP Varun Gandhi had sought the details of the region-wise decrease in the water table across India since 2000. (Photo credit: ANI)

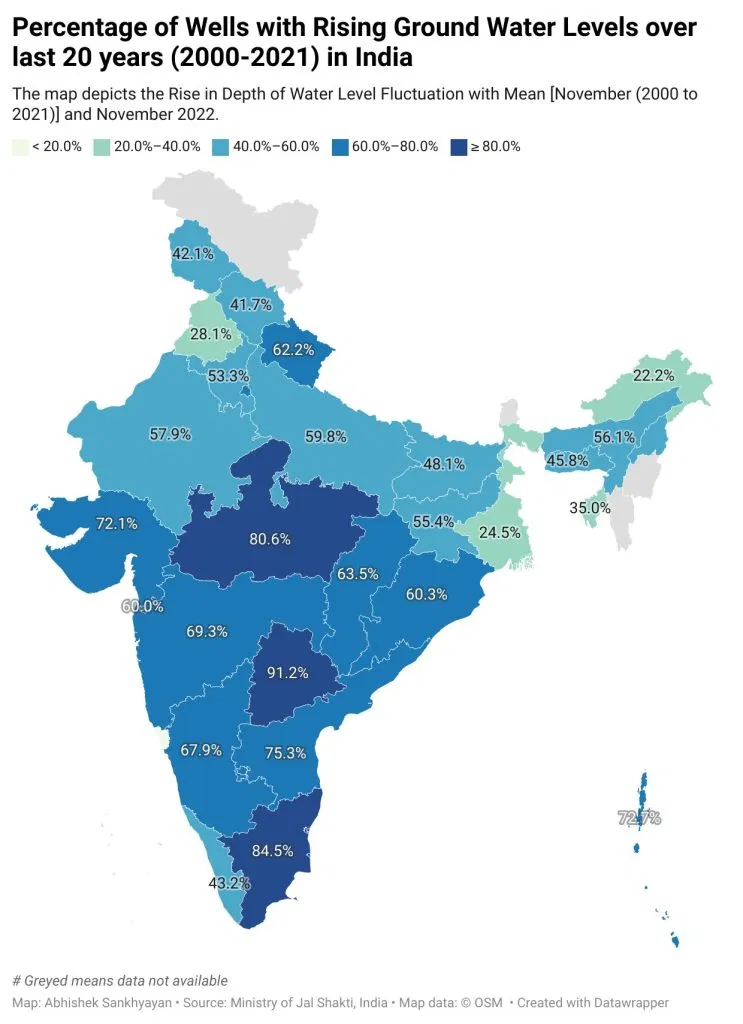

New Delhi: The Ministry of Jal Shakti has claimed that groundwater status in the country has improved overall, based on data from 2000 to 2022. 65.6% of observation wells registered a rise while 34.1% registered a fall in groundwater levels.

“Further, in order to assess the long-term fluctuation in groundwater level, the data collected by the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) during November 2022 was compared with the mean of November 2000 to November 2021. This analysis indicated that about 38.4% of the wells monitored have registered a fall in groundwater levels while 61.6% of the wells have registered a rise,” the Minister of State for Jal Shakti Bishweswar Tudu said in reply to a question raised in Lok Sabha.

MP Varun Gandhi had sought the details of the region-wise decrease in the water table across India since 2000 and if the government had taken any measures to conserve water and thereby reduce the rate of decline in the water table across the country.

What does the analysis reveal?

The Ministry carried out a simple comparison, i.e. comparing the fluctuation of water level in November 2022 with November 2000. It also carried out a comparison of water level fluctuation between November 2022 data with the mean for 2000 to 2021.

The data from the simple comparison showed that 88.2% of observation wells in Gujarat, followed by 83.5% of wells in Telangana, and 82.7% in Tamil Nadu showed a rise in water levels. Of these, 49.9% observation wells in Gujarat showed a rise of water level of 4 metres or more (the other two categories being 0-2 metres and 2-4 metres).

Goa led the list of states showing a fall in water level of observational wells (80.6%), followed by Arunachal Pradesh (80.0%), West Bengal (67.8%), and Punjab (67.1%). The Union Territory of Chandigarh was the worst performer with 100% of its observation wells showing a fall. As much as 50% of them showed a fall of water level of 4 metres or more (the other two categories being 0-2 metres and 2-4 metres), the data said.

Further, the result came out more granular when it came to comparison between mean of water level fluctuation between November 2000 to 2021 and November 2022. The top three states where the wells showed a fall in water level are Goa (85.7%), Arunachal Pradesh (77.8%), and West Bengal (75.5%). As many as 78.6% of observational wells in Chandigarh, too, showed a fall.

With 91.2% of its observational wells showing a rise, Telangana topped the list of states with increased groundwater level, followed by Tamil Nadu (84.5%), and Madhya Pradesh (80.6%), these being total for 0-2 metres, 2-4 metres, and 4 metres and above.

What makes Telangana march ahead and Goa fall behind?

Since 2014, when the state was bifurcated from Andhra Pradesh, Telangana has given high impetus to the irrigation sector, experts said. Of the multiple schemes that were implemented, at least 4-5 have shown measurable impact.

“For instance, more than 27,000 Kakatiya era tanks (centuries-old water bodies from the Kakatiya era) out of 45,000 were restored and rejuvenated. Multiple bigger reservoirs were built as part of the Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation scheme. After using link canals, it ensured that 10,000-plus smaller tanks were always filled. Then there were 1,200 or more major check dams built across the state,” said Dr Pandith Madhnure, former director of Telangana State Groundwater Department.

“Telangana also went ahead with two of its flagship water conservation schemes: Mission Bhagirathi, wherein the focus was on ensuring surface water so that people’s dependence on groundwater decreased, and Haritha Haram programme that saw massive plantation drive,” Madhnure said.

Goa, on the other hand, said experts, has fallen prey to its increased tourism that relies on groundwater extraction. In fact, 37% of the hotels in Goa use groundwater and 25% buy it from tankers, who in turn, get it from wells, effectively from groundwater, said a 2017 research paper.

Road ahead for groundwater management

Varun Gandhi’s questionnaire also mentioned if there is a proposal to update the current framework for groundwater management to tackle the challenges related to the decrease in water table.

The Ministry launched the Jal Shakti Abhiyan in 2019, a time-bound campaign with a mission mode approach that intended to improve water availability, including groundwater conditions, in the water-stressed blocks of 256 districts in India. In August 2019, the Centre also launched Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) which seeks to provide potable tap water supply to every rural household by 2024.

Water being a state subject, under JJM, it has been mandated for the States to carry out activities for source recharging, viz. dedicated borewell recharge structures, rainwater recharge, rejuvenation of existing water bodies, etc. by adopting watershed/spring-shed principles, in convergence with various Central/State government schemes.

The Ministry had circulated a Model Bill to all the States/UTs to enable them to enact suitable groundwater legislation for the regulation of its development, which also includes the provision of rainwater harvesting. “However, so far, only 19 States/UTs have adopted and implemented the groundwater legislation,” said an officer from the Ministry.

Going by the adage, ‘if you can measure, you can conserve’, the Centre has been planning the upgradation of its available data resources.

The CGWB has prepared the aquifer maps of the entire mappable area of the country, including determining the aquifer characteristics and their management plans by using the latest survey techniques under the National Aquifer Mapping Programme (NAQUIM 1.0). “In phase I, we have already mapped 25.15 lakh sq km of area out of 32.8 sq km. The scale is 1:50,000 for this mapping,” Subodh Yadav, Joint Secretary in the Jal Shakti Ministry told News9 Plus.

The management plans have already been shared with States/UTs for suitable interventions.

“In phase II, we would be undertaking mapping at a higher resolution, say, 1:5,000 and 1:10,000. That will give us a better idea of overexploited areas, critical problems, etc.,” Yadav stated.

In fact, the CGWB has taken up aquifer mapping (NAQUIM 2.0) at varied finer scale in 11 types of identified priority areas. These have been identified based on groundwater-related issues/criticality of groundwater situations like water-stressed areas, urban agglomerates, coastal areas, industrial cluster and mining areas, areas with spring as the principal sources, areas with deeper aquifers, groundwater contamination, auto flow zones, canal command areas, areas with poor groundwater quality, etc.

“First year of the five-year NAQUIM 2.0 is done. We hope to achieve better in the remaining four,” Yadav added.

(This story first appeared on news9live.com on Aug 14, 2023 and can be read here.)