Infosys employee’s death shows Bengaluru has not learnt its lessonInstances of floods in the city are rising as its lakes, which absorb rainfall, are being destroyed.

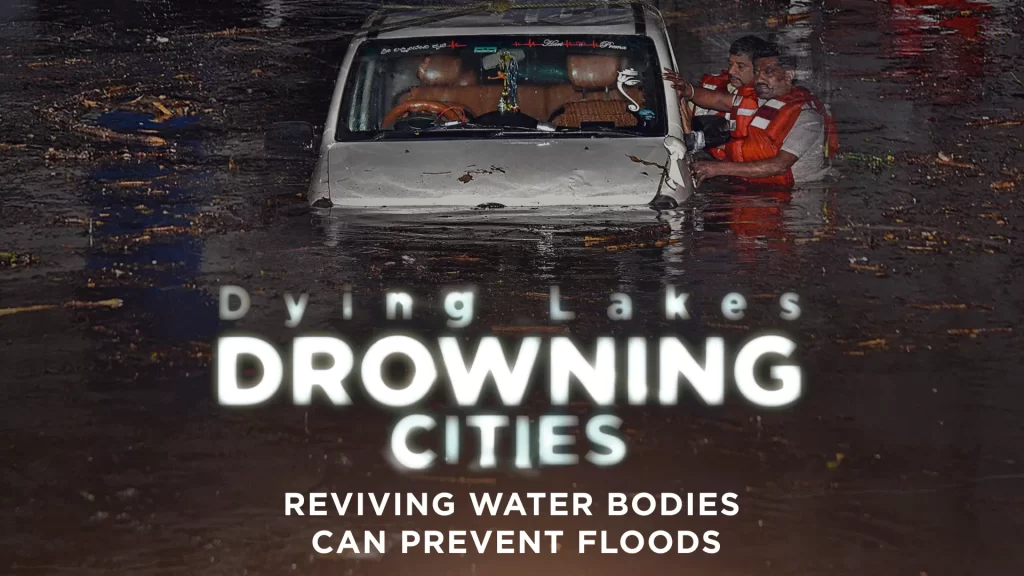

Drowning cities (Photo Credit: News9)

To watch the series click on the link

When Bengaluru received 50 mm of rainfall in just about an hour on Saturday, a 22-year-old Infosys employee drowned after her car got stuck in a flooded underpass. Even as the blame game continued, cars piled up due to waterlogging, some buildings collapsed and scores of trees were uprooted. The strong pre-monsoon showers brought back the grim memories of what the IT hub had witnessed last year.

In September 2022, Bengaluru—a city known for its water bodies—was battered by rains and Bellandur lake overflowed, causing massive flooding. While Bellandur Main Road faced severe waterlogging, water rose to 8-10 feet in Yemluru, a plush colony of duplex bungalows, and people had to be rescued with a tractor trolley.

After the initial shock, came the realisation that the areas that saw heavy flooding were built upon a water body, lake, or the connecting water channels, called ‘raj kaluves’.

Unfortunately, Bengaluru was not alone. The year 2022 saw several cities, including Pune, Hyderabad, and even Delhi-NCR, go under water. As the cities are growing faster, urbanisation is gobbling up open spaces and water bodies. A little more than normal rain causes flooding because the absorbing wetlands and water bodies have been destroyed.

Prof TV Ramachandra from Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, points out how the water bodies and greens paces in the city are dying. “The city of 715 sq km way back in the ’70s had 68% green cover. About 8% was under the buildings. And today, 85% is under buildings, concretised. Green, open spaces, which are the sink for the rainwater, are less than 3%,” he says.

Ramachandra and his team had carried out a study in 2016 that found that 98% of lakes in Bengaluru have been encroached while 92% have untreated sewage and industrial waste flowing into it.

Other experts also point out that in urban jungles such as Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and Delhi, it is not just the connecting rivulets or channels that have gotten destroyed or encroached, but the lakes themselves have become urban property with huge structures built on them.

For example, Kolkata’s 2006 map published by the National Atlas and Thematic Mapping Organisation (NATMO) showed 8,500 water bodies. “But my research shows the number today is around 4,800. So, in the last three or four decades, nearly 4,000 water bodies have vanished in the city,” says environmentalist and author Mohit Ray.

Delhi, too, had 1,200 water bodies till about 100 years ago. Only 650-odd remain today.

These water bodies help collect and divert rainfall into the soil to replenish groundwater levels. No wonder then that when lakes vanish, the water finds its way into homes and underpasses, drowning cities.

“These water bodies provide us with a lot of ecosystem services. Not only the recharge, but as part of the adjustment to climate change. They provide a cooling impact. They are also carbon sinks,” explains Manu Bhatnagar from the Natural Heritage Division of Indian National Trust for Arts and Cultural Heritage (INTACH).

However, it is not just a question of the number or size of water bodies, but also of the water quality. “People dump solid waste in lakes. The storage capacity of lakes decreases. Buildings and dumping of solid waste has encroached even the ‘raj kaluve’. These hindrances are creating or aggravating the flooding situation in Bengaluru,” Ramachandra adds.

This is what had happened with the Shamsi Talab in Delhi. “It used to be a good lake 30 years ago, but over the last 15-16 years, the degradation of the lake happened. Now we are looking for a solution, such as a sewage treatment plant, which will treat sewage going directly into the lake,” says Lalit Gupta, who heads the Shamsi Talab Residents Welfare Association (RWA).

“This threat exists in many cities where water body land is seen as real estate. Planners do not understand that water bodies are to be seen in integration with their watersheds,” Bhatnagar explains.

Speaking about Hyderabad, Dr Lubna Sarwath, academician and social activist, states, “Hussain Sagar and Himayat Sagar are the two designated drinking water resources of Hyderabad. More than a hundred encroachments have been identified in each of the reservoir.”

Pointing out that the authorities are apathetic towards protecting water bodies, Sarwath says, “There is no rule for the government. It is very proactively concretising the water bodies.”

“The time has come for us to be living in partnership with nature, and not at cross-purposes with it. We can’t dominate nature. Ultimately nature will strike back and will extract its pound of flesh,” says Bhatnagar.

(This story first appeared on news9live.com on May 25, 2023 and can be read here.)